The budgets of geek movies have skyrocketed. Is this a good thing?

It's a little shocking how big the budgets are. And concerning.

It’s hard to overstate the amount of money that Hollywood has been pouring into movies and TV shows that comprise a huge chunk geek culture. Star Wars movies, the MCU, the DCU/DCEU, Star Trek TV shows, video game-based movies…For the past couple of decades, studio executives have opened the spigots to feed a relentless stream of geek-based filmmaking.

We all have a gut feel that the growth has been big. It’s particularly obvious for someone like me, who grew up with far less geekery on the big or small screen. A lot of what was aired or screened was, to be polite, of mixed quality. We were grateful for movies as mind-blowing as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet Of The Apes. We were also so desperate that we watched The Star Wars Holiday Special and yet another goofy episode of The Incredible Hulk. That’s clearly not the world we live in now, where science fiction and other geek genres are more the rule, less the exception.

But exactly how big is geekery in Hollywood now? And what might have been the costs of this explosive growth?

Science fiction films, by the numbers

To answer that question, I did some research. The science and math nerd in me is always thrilled for any project that involves spreadsheets. That part of my brain is also excited to purchase new office supplies. I yam what I yam.

I narrowed my focus down to science fiction movies of my youth, in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, which we’ll call the classic age of SF movies. I also gathered the same information about the modern age, comprising the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s. I could have included films based on other genres (fantasy, comic books, horror, video games, etc.), but I kept the focus, with one exception, on science fiction. (One comic book movie is in the list. It certainly has some SF elements, and it’s hard to talk about contemporary geek movies without some mention of the MCU.)

The important data points, therefore, are the following:

How big was the budget for each movie?

How much money is that, measured in 2025 dollars?

Obviously, the choice of movies is important. The list includes movies with big budgets, and also small ones, from both eras. We’ve all enjoyed offerings from both the leviathans that loom over geek culture, such as Star Wars, and more modest productions, such as The Road Warrior or Moon. In fact, the unexpected breakout hits often become the leviathans. Star Wars was once an oddball film that, in 1977, made most people wonder what all those people were lining up to see, and why.

Aside from size, the other important consideration for selecting the list was quality. For the first cut at this question, I didn’t want to muddy the proverbial waters with a mix of good and bad movies. Therefore, I accentuated the positive, movies I’ve certainly enjoyed, and certainly have worked for other fans as well. Some of them may not be your cup of tea, but I had to start somewhere. And since, according to Einstein, no frame of reference is privileged in the universe, I’ll pick mine, for now.

Also, I’m only including the production costs, not the marketing costs. In case you don’t know, marketing movies today is a very expensive affair. It’s why recent movie like James Gunn’s Superman or The Fantastic Four can make hundreds of millions of dollars in their first weeks, exceeding their production budgets, and still be considered box office “failures.” Studios need to recoup all their costs, including their marketing, and the cut they have to give to theaters. The question I posed is, how much are studios willing to spend to make geek movies, not how much it costs to distribute them and get people into seats.

Finally, I have to acknowledge, the studios publish production budgets that are not always accurate. They have their reasons, from arcane accounting procedures, to covering up expensive flops that got out of control. However, the stated budgets are at least in particular neighborhoods, some in a higher price bracket, some in a lower one. In that respect, the numbers are still useful for our purposes, even if a studio might have overstated or understated the production costs for a particular movie.

So, just to recap, here’s how we’re keeping the variables to a minimum:

Science fiction movies only.

From two time periods, the 1960s through the 1980s, and the 2000s through the 2020s.

Both big-budget and small-budget films.

Higher quality films only.

No marketing or distribution costs.

The official budgets are reliable enough, for our purposes.

Now, let’s look at the movies.

Twenty examples of classic and modern geek cinema

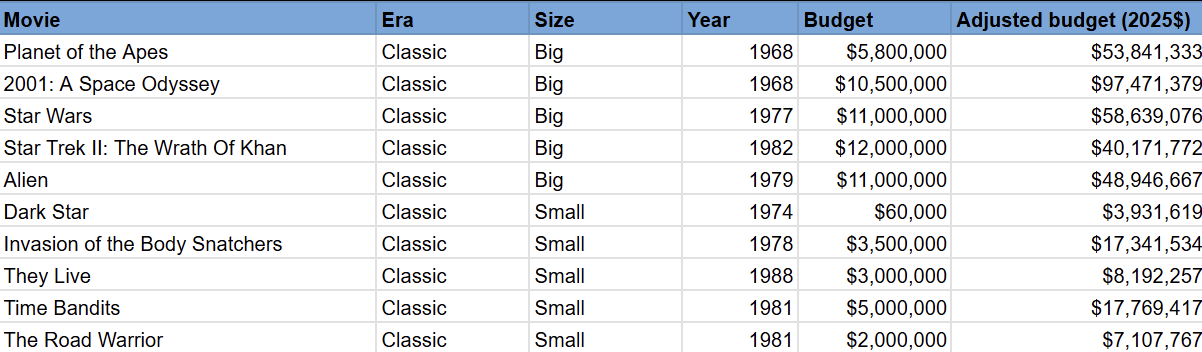

Here are the films from the classic era of SF films:

As far back as the 1960s, SF movies could be a Very Big Deal. 2001 was considered high art. Planet Of The Apes had one of cinema’s biggest twist endings. Star Wars and Alien practically defined their own subgenres. And even some of the smaller movies, such as They Live and The Road Warrior, have enduring appeal today. Star Trek II pulled the franchise back from the brink of increasing indifference from Paramount.

Dark Star might seem like an extreme outlier, a shockingly inexpensive movie. It was John Carpenter’s student film, turned into a theatrical release. George Lucas’ THX-1138 followed a similar trajectory, albeit with at least one recognizable star, Robert Duvall. There’s an inexpensive outlier in the modern list, too, so Dark Star doesn’t unbalance the list. Plus, I like promoting lesser-known films. That instinct is in the DNA of every movie geek.

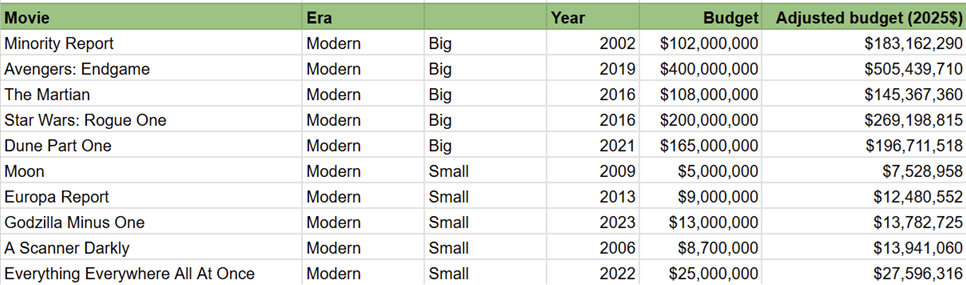

All that said, here’s the modern SF film list:

There’s a Star Wars movie in that list, and not one of the ones that would make you bleed from the eyes if anyone were to force you to watch it again. There’s one superhero movie, Avengers: Endgame, which certainly had time travel, powered armor, and other science fictional elements. It was also a turning point in geek culture, proof that someone could actually do a massive cross-over storyline, like the Infinity Gauntlet series that inspired it, and stick the landing. As seminal as Star Wars (space opera for a mass audience), 2001: A Space Odyssey (hard science, Big Think SF for a mass audience), or Alien (science fiction plus horror for a mass audience) were, in their time.

The incredibly cheap film in this list, for a modern SFX-heavy movie, is Godzilla Minus One. The visuals are stunning, making Godzilla into a terrifying figure at a level that even the best “suitmation” never fully achieved (except for maybe the 1954 original, for its time). It’s just as impressive a film, in that respect, as the recent Star Wars, Star Trek, or superhero movies. And it was made on a pittance, a mere $13 million. The other small movies on this are just as good from practically every angle (SFX, story, acting, etc.), but Godzilla Minus One appeared just as worries about inflated movie budgets were getting louder.

The big movies on this list had a lot of mass appeal, beyond just the Star Wars and MCU examples. Minority Report had Spielberg, Cruise, and fast-paced action. The Martian was fun for many people, not just SF fans, to see Matt Damon “science the shit out of” his predicament. Dune Part One proved more appealing than tripping balls with David Lynch during his version of Arrakis, back in the 1980s.

Now we can get a sense of how big the big movies were, and how small the small movies were. How much has the landscape changed between the two eras, when geek culture existed in the fringes, and now that it’s in the mainstream?

Geek movies go Nieman Marcus

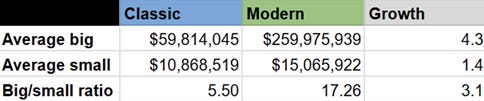

The short answer is, quite a lot.1 The bigger movies are way bigger now, relative to the smaller ones. While all movies may be more expensive to produce these days, geek movies have ballooned at a startling rate:

Reading from left to right, we see the growth for each category of movie, big and small, from the classic era to the modern one. While the smaller movies have increased a small amount, the budgets for the would-be blockbuster extravaganzas have grown fourfold. As the saying goes, a hundred million here, a hundred million there, and suddenly, you’re talking about real money.

The budget gap between the bigger and smaller productions has also grown like CEO salaries in the same era. A movie like Planet Of The Apes was always going to dwarf a less prestige venture like They Live, so a 5.5 average budget multiplier is no surprise. A 17.26 average multiplier for the modern era, however, is a bit of a shock.

Let’s look at the same issue, using Godzilla Minus One as our baseline for inexpensive geek movies in the contemporary era. How many times larger is the budget for our sample films than Godzilla Minus One? Or, to put it another way, how many Godzilla Minus Ones could you produce for the cost of these budgetary behemoths?

I enjoyed Avengers: Endgame a lot. It had its flaws, but for the most part, it was an extremely enjoyable roller coaster ride. It was also major cinematic achievement, on par with, or exceeding, the ambition of Peter Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings trilogy. But did I enjoy or respect it 36.7 times more than Godzilla Minus One? Heck no.

Bad times for big budgets

It has been great times for geek culture, thanks to the studios’ willingness to fund geek movies to this level. I finally got to see Thor, one of my favorite superheroes from my youth, swing his hammer in a way that I my younger self thought was never going to happen on the screen. I loved that Star Wars occasionally broke out of its very narrow mold, as it did with The Mandalorian and Andor, and have the budgets needed to make these new kinds of stories succeed. I’ve been grateful that Philip K. Dick has been the source material of blockbuster movies like Minority Report, introducing people to the disturbing but important notions that permeated his writing.

But there’s a cost to this era of kaiju-sized budgets that goes beyond just the money spent.

In 2025, geek movies featuring popular science fiction properties are not money-printing machines. There’s a lot of talk about growing indifference to new Star Wars stories, complaints about “nuTrek,” and superhero fatigue. The wave of mass enthusiasm was probably going to crest naturally, just as the enthusiasm for the original Star Wars trilogy began to fade. For most people who aren’t diehard fans like you and me, you can only hit the same neuron so many times.

But there are other problems with the movie and TV industry that go beyond the natural lifecycle of fads, crazes, and trends. Hollywood has always beaten fads to death, but not always with a gem-encrusted, solid gold hammer. The amount spent on geek movies is a choice, not a necessity. Apparently, that’s not what the current studio executives think.

Instead, they are following the same escalation logic that US leaders followed to catastrophe in the Vietnam War: if the problem is that the current strategy is not working, then just do more of it. The solution for Star Wars is movies with even bigger budgets than the TV shows. The solution for Star Trek is more expensive Trek shows. The solution for the MCU is another mega-Avengers event. Escalate, escalate, escalate. And the more they escalate, the more important each mega-movie is for the fortunes of the studio…

Fortunately, there are other strategies to pursue. Many of them involve de-escalation. Here are a just a few examples:

Tell smaller stories that require smaller budgets. Remember when Batman was just fighting the Joker and a few other Arkham Asylum escapees? Those were good movies, without the entire universe being in jeopardy.

Write stories that are not non-stop action sequences, giving time for characters to develop, to the point that we actually care what happens to them on the screen. You’ll save money on stunts, CGI, and other costs for turning every movie into Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride On Adderall And Shrooms.

Stop assuming that the more CGI you put into a movie, the more attractive it will be to look at.

Stop putting relatively inexperienced directors in charge of complex, expensive films and TV shows with thousands of moving parts. Make the movies less challenging to produce, and increase the skill level of the people running the show.

Have a finished script for your next movie, and a roadmap for the next movies in that series. It’s unbelievable that, after the debacle of the last Star Wars trilogy, studios seem not to have absorbed this lesson.

We can summarize these and other suggestions in a neat package: start making more medium-sized movies. They’ve all but disappeared from Hollywood, to Hollywood’s detriment. Medium budget movies still allow for a lot of what the big budget films hope to achieve, but at less cost, and also less risk. If a particular director proves to be unsuited for the assignment, a particular character less popular than hoped for, a particular new type of story baffling to audiences, then you can retreat and regroup. You don’t have to go into panic mode, with reshoot after reshoot to try to spread more peanut butter over an unsavory sandwich.

Aside from being a fan of geek culture, I’m also a big film noir buff. During the heyday of film noir, in the 1940s and 1950s, studios produced noir thrillers that ran the gamut from low budget features, with extremely tight budgets and unknown actors, to big-budget ventures with marquee directors and actors. And there were lots of movies between those two poles. During this period of amazing creativity, classics emerged from all of these strata, including no-budget movies like Detour, medium budget films like Touch Of Evil, and prestige films like Key Largo. Film noir had a healthy ecosystem in which filmmakers could hone their craft, experiment, and adjust. Not every time at bat had to be a home run, or the studio would be at risk.

As my good friend and co-host Steven often reminds me, at the end of the day, the people in the book, comics, movie, and TV industries all need to make money. We can critique quality, but that’s a luxury we can enjoy because the people behind the geek culture can afford to pay their bills.

But ultimately, quality matters from a business perspective. When we did an episode about Star Trek The Motion Picture, I cited the Theory Of Constraints, the notion that art sometimes needs to work within some guardrails, including financial ones, to produce something worth your precious movie dollars. Constraints inspire creativity, as we discussed in past episodes about monster movies from the 1950s, Doctor Who, and other geekery that we love. Too much money can make “creatives” a bit stupid, willing to rely on expensive and unnecessary adornments, much like the Homermobile in a classic episode of The Simpsons.

As much as I love geek culture, I’d hate for geek moviemaking to be crushed underneath the weight of movie budgets. That’s bad, in the long term, for everyone, producers and consumers alike.

I’m is co-host of Ancient Geeks, a podcast about two geeks talking about what it was like to become a fan of SF&F, comics, and other aspects of geek culture when it was all new and slightly disreputable. Look for us on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, and other podcast sources.

And check out my co-host Steven’s excellent post on the popularity of different Star Trek series and episodes. Another adventure in spreadsheets!

The rate of growth has been significantly more than mainstream (i.e., non-geek) movies. I may post a follow-up with these comparative data.

The Planet of the Apes 1968 budget reads $58 million, and the adjusted 2025 budget reads $53.8 million.

Doesn't seem right.