Open ecosystems versus closed gardens

Geeks versus suits

[If you enjoy stories of greedy corporate executives getting their comeuppance, read on. No interest in tabletop role-playing games required.]

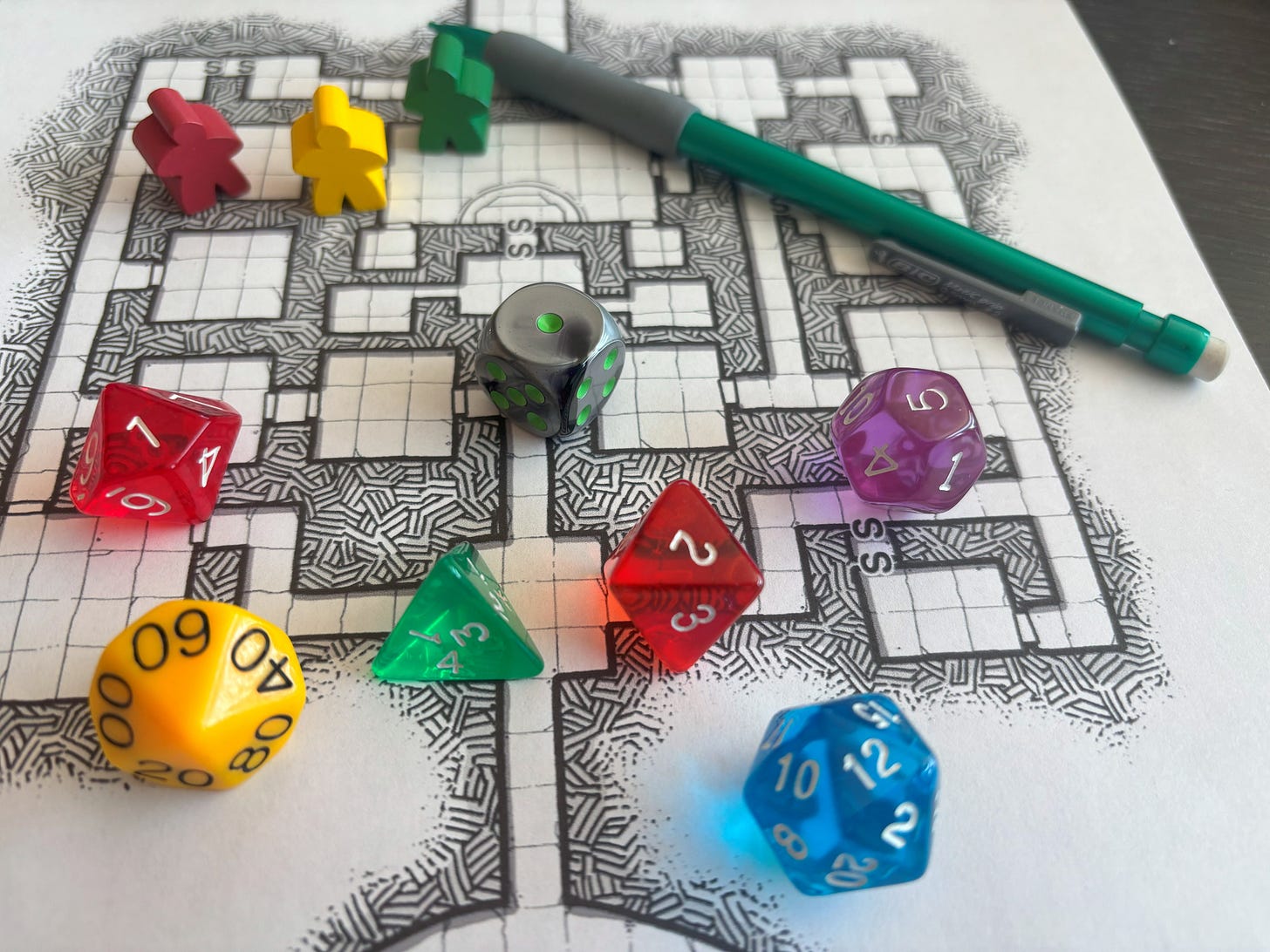

I’ve been continuing to explore a solo role-playing experience, using the Shadowdark rules. Our three heroes, Falc, Gerlant, and Rokurf, have survived getting lost in the wilderness, being attacked by angry peasants, and nearly sucked into a midnight battle between fanatic cultists (is there any other kind?) and hyena-headed humanoids. They’ve arrived at the Vault of the Forbidden Elephants, and made their first foray into the dark labyrinth.

Since this whole solo RPG thing is new to me, I regularly put the game on pause to get some help. I needed a better approach to populating the Vault with monstrous opponents, determining what was in each randomly-generated room, and ultimately determining where the object of their mission, the Infernal Armor of Blood, would be found.

Fortunately, there was a lot of resources. Advice from other Shadowdark solo players. Tables of random room contents developed not just for Shadowdark, but other RPGs like it. Even some already-generated maps that I could make the layout of the Vaults. All available for free. I would have gladly paid for some of it, too. Not surprisingly, there are publishers out there who are glad to sell these sorts of game aids, and lots more.

This kind of free-wheeling experience, drawing on many sources, is at the heart of role-playing games. It’s what made it fun when I first started playing, back in the days of the Dungeons & Dragons “white box” set. Lots of ways to get help, if your own imagination or patience isn’t up to the challenges facing the person in charge of running the game. Much of it inexpensive, or free. You basically pay whatever you want. It’s your game.

Unfortunately, that’s not the philosophy that the company behind the most famous, most successful role-playing game, Dungeons & Dragons, pursued recently. They tried to create a very different, very limited game experience, motivated by a drive to “monetize” D&D. And by pursuing this strategy, they reached into the corporate closet, pulled out the proverbial shotgun, and shot themselves in the equally proverbial foot.

When I first discovered Dungeons & Dragons, the nascent hobby of role-playing games had a very welcoming, laissez faire spirit. If you wanted something more than what the publisher, TSR, had for sale, there were lots of other companies who were happy to help. When I took the role of Dungeon Master, I could mine third-party publications from publishers like Judges Guild for ready-made plots, villains, locations, and loot. If I wanted a monster for the players to battle that wasn’t familiar to them, there were amateur publications, including zines like All The World’s Monsters and Alarums & Excursions from which I could summon one of these bizarre and hostile creatures. (Heffalumps! Nerve Flayers! Killer Bees!) If I wanted to expand the rules to include new classes of heroes, new magical artifacts, or even provide more color when the protagonists plunged into battle, there were other sources, like The Arduin Grimoire, from which I could draw.

Or, since there was a strong DIY element to early role-playing games (RPGs), I could also invent any of these things on my own. D&D and other RPGs were toolkits you owned, so you could do whatever you wanted with them. Improvisation, invention, and ecumenicism were encouraged, not just among hobbyists, by the publishers themselves. Practically every RPG, starting with D&D, has made a point in the rulebook to say, “This is your game. Do with it what you will.”

Once the RPG industry expanded, some publishers started to look at this diversity with a jaundiced eye. Why are these geeks spending money on products from other companies, when they could be buying from us? Mostly, publishers played fair in this regard, providing attractive alternatives of their own. TSR published hundreds of packaged adventures, monster manuals, rules expansions, and other supplemental material, but the third party market of D&D-related publications remained healthy.

But some companies eventually did get quite anti-competitive about it. Games Workshop, the producer of popular miniatures battle games like Warhammer and Warhammer 40,000, started to insist on trapping their players in a walled garden. It was quite attractive in that garden, with all the amazing-looking figurines, a kaleidoscope of paints for them, crazy fantasy and science fiction factions, and striking-looking terrain to stage miniatures battles. However, Games Workshop insisted, you had to buy it all from them. If you wanted to be a true GW fan, playing in GW-sanctioned games in GW stores or GW-organized events, then you had to buy it all from them. And that’s true through today.

Fortunately for fans of the medium, role-playing games are qualitatively different than miniatures battle games. All you need to play a role-playing game is a set of rules, some dice, a few office supplies (pencils and maybe graph paper), and some friends. The only thing you had to buy from a publisher like TSR was the rules — and even those you change, expand, or replace yourself, either with the help of other companies, or through your own innovation (“home brew” or “house” rules). The intangibility of role-playing games helped keep the hobby competitive, unlike the Games Workshop miniatures battles, which required physical components (miniatures, paints, terrain, rulebooks) to play. No RPG publisher could limit your imagination, or the collective imagination of you and your friends. That imagination was the core of the game.

(Side note: Miniatures have always been a big part of role-playing games like D&D, too, but they were purely optional. I always liked miniatures, but I happily used a die or an eraser to represent a slavering troll if I didn’t have that particular miniature.)

The ontology of role-playing games, therefore, was a boon to the industry. No company, not even the giant of the industry, TSR, could pull a Games Workshop on the hobby. This openness was good for both publishers and players alike. When new players saw the big, bustling marketplace of RPG products, they felt as though they were joining an exciting hobby. Even though playing an RPG was a new experience, there was plenty of help available, in the form of packaged adventures, tools like “battle mats” (roll-up sheets on which you can draw a map with erasable markers), and plenty of other game aids they had never imagined before. Once you were a full-fledged RPG geek, there was always something new and intriguing — new adventures, new options for D&D, new RPGs other than D&D, shiny new dice, new miniatures, new everything. Third-party vendors were helping customers stay engaged with D&D, by supporting D&D in particular, and the RPG hobby in general.

TSR struggled with this economic principle for a while, but eventually came around to embracing it. They created an Open Gaming License (OGL) that set some ground-rules for third-party partners. Fine, go ahead and create new material for D&D, or even create D&D-like games. But here are some guidelines to ensure that you’re not producing anything that might hurt the D&D brand, the central tent pole for TSR’s business.

That happy situation did not last. Eventually, D&D fell under new management, through a series of buy-outs. A few years ago, the higher-ups in the new parent company, Hasbro, decided to reject the “rising tide raises all boats” philosophy behind the OGL, opting instead to try to build the type of walled garden that Games Workshop has erected. Since some of the new executives had been recruited from video game companies, their strategy was to turn D&D into a computer game (Creative thinking, Smithers!), where they could charge subscription fees and control access to a limited set of materials that Hasbro itself produced. They had already moved a lot of D&D content online, even buying a precursor tool to play D&D online, but nowhere near as restrictive as the new platform would be. Therefore, that platform, One D&D, did not seem like a big stretch. At least, in their heads.

Hey, kid, you want to play D&D: everything is on a computer, online. The rulebooks, dice, maps, miniatures, even your friends — you have to be sitting at a computer for all of it. Your friends, too. And you have to pay us a monthly subscription fee. And you have to keep buying things from us, and only us, to add new rules options, new monsters, new miniatures, new everything. Maybe we’ll even throw in an AI-generated Dungeon Master. But don’t try too much of that homebrew nonsense, our programmers can’t provide that flexibility. Sounds great, right?

The actual result was, very happily, and not at all surprisingly, abject failure. The digital platform proved to be a bust. Not only did no one really want it — playing with our own rulebook, dice, paper, pencils, and friends is just fine, thank you very much — but there are plenty of other RPGs to play, in the old-fashioned way. Sure, we RPG gamers might want to use a digital platform like Roll20 to play online, when we’re not physically in the same room. But we want the game to be ours.

Hasbro had already alienated many of its customers, pursuing an aggressive, anti-competitive, “listen only to us, buy only from us” strategy that the company felt was needed to squeeze more money out of customers. They threatened independent YouTube channels that were previewing (i.e., marketing) new Hasbro/Wizards Of The Coast products. They sicced the Pinkerton agents on someone who had a preview version of some cards for Magic: The Gathering. They planned to demolish the Open Gaming License, crippling and maybe even destroying the third-party market, but then had to retreat temporarily after major backlash. Short of twirling their moustaches and chuckling evilly while they stole from widows and orphans, they could not have done a better job of painting themselves as money-grubbing villains. Just as catastrophically, they became a company that you’d find featured prominently whenever you looked up the word enshittification.

D&D’s future is in question. Hasbro wants increasing profits, but their chosen way of pursuing them — which, by the way, replicate some of the most obnoxious tactics of the computer game industry — has imploded. Where D&D goes now is unclear. Maybe it will be spun off or sold to another company. Maybe it will atrophy, while other RPGs fill the void. Maybe the suits will have an epiphany and try to re-establish D&D as a huge part of an open ecosystem. I wouldn’t bank on that last option, but who knows. (For a good video that goes into more detail about Hasbro’s digital disaster, click here.)

Meanwhile, people like me can continue to play RPGs in whatever way we want: with friends, or solo; in person, or online; as diehard fans of a single publisher, or as people with more eclectic takes. I’m just grateful that, when I got stuck playing Shadowdark solo, needing more than I got from that publisher, there was a vast ecosystem of support available. That’s almost the definition of a healthy hobby.

As a historical note, the first OGL came after TSR was acquired by Wizards of the Coast. It was propagated as part of 3rd Edition D&D, which was a very welcome revision and simplification of the rules as we knew them. It got rid of THACO! And mirroring the open source movement in software, they published the OGL.

It was a great move. They sought to build an ecosystem that had them in the middle.

This story, the story of TSR under Lorraine Williams and how it ended up being sold, is told quite well in https://www.amazon.com/Slaying-Dragon-History-Dungeons-Dragons/dp/125027804X

I highly recommend it.

The Hasbro purchase came much later. I find myself wondering how much their business was hurt, and what alternatives the hobby is leaning into. Maybe Pathfinder? I don't really know.